| Carving Life into the World’s Hardest Stone | |||||

| by Amy Lilly | |||||

|

|||||

Heather Ritchie is the first to admit she’s petite. “I’m a tiny creature,” quips the self-possessed 38-year-old from Plainfield. She is standing in the vast manufacturing shed of Adams Granite Company in Barre. Her loose plaid flannel workshirt, baseball cap and steel-toed boots add about as much bulk to her as they would to an Alberto Giacometti sculpture. It’s hard to imagine that such a creature makes her living carving granite, one of the world’s heaviest types of stone. With a grant in 2012 from the Charles Semprebon Fund’s Stone Sculpture Legacy Program for Barre’s public spaces, Ritchie created Coffee Break, a grouping of benches on Main Street sporting the life-sized lunchbox, coffee mug, hand tools and paper hat of 19th-century granite workers. Last year, Ritchie and four other carvers won an Art in State Buildings commission to provide sculpture for the newly built Vermont Psychiatric Care Hospital in Berlin. Ritchie carved a bench in the shape of a beaver dam, complete with a beaver peeking over the edge, for an interior courtyard. And, thanks to a second Semprebon grant, she is currently at work on a bike rack, featuring a life-sized big-wheel tricycle angled up a ramp at one end. Next spring, the piece will be installed in Charlie’s Playground near the Barre public pool.

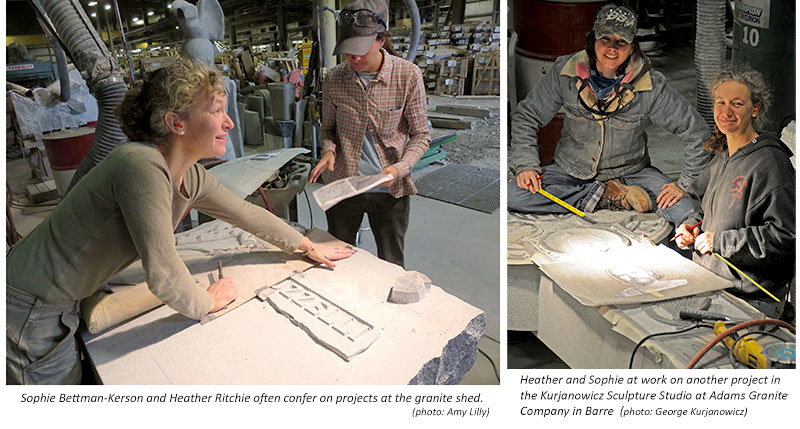

On a recent morning, Ritchie walks Vermont Woman through Adams’ manufacturing shed, where she makes memorials for the company and carves her own work. Unfazed by the near-deafening din of the overhead granite-dust vacuum and compressed-air systems, she picks her way through the 70,000-square-foot shed’s operations, from the front office to her carving station beside the rear loading dock. Her slight figure contrasts starkly with the hulking cranes and saws, multiton hunks of granite, and rows of rough-cut memorial stones. But it’s not her size that makes Ritchie stand out in the industry—or among the dozens of co-workers she passes on the way to her studio, all of whom are men. It’s the fact that she’s female. Ritchie and her colleague Sophie Bettman-Kerson, a part-time carver at Adams who works as a licensed nursing assistant, are the only women carvers currently working in what is known as Barre’s memorial industry—the 20-odd granite sheds that produce mostly Roman Catholic headstones and cemetery statuary. And, given that few of Barre’s carvers operate outside the industry because of the daunting overhead costs of setting up a carving studio, Ritchie and Bettman-Kerson are also pretty much the only women carvers around. That has made for some uncomfortable situations, including that return walk through the manufacturing floor to the shed’s only bathroom, in the office. “You don’t want to be on parade," Ritchie explains. “There are times when I’d rather get in my car and go use the bathrooms at the ball park.” Fending off looks and preconceptions from the men around her has been, she admits, “a lot of extra work." But it’s work she has learned to handle along with her sculptural work. “People give you looks and snickers and stuff," she says calmly, “but when they see your work on the washstand, they respect you.” |

|||||

The granite of Barre began to attract expert carvers from around Europe in the late 19th century—men who helped establish the town as “the granite capital of the world." Ever since, the industry has been almost completely male and except for a few women currently employed as etchers, it still is. Because carving is learned largely through apprenticeship with an established carver, Ritchie and Bettman-Kerson had no access to female mentors. None existed. But they did find George Kurjanowicz, a Polish-born sculptor with an unusually gender-blind approach to imparting his skills. Kurjanowicz apprenticed with Korean War Memorial sculptor Frank Gaylord and began taking on his own apprentices in the late 1990s through the Middlebury-based Vermont Folklife Center’s Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program. The grant program funds four-month apprenticeships, ensuring that traditional arts continue to be passed down. Kurjanowicz has had five such apprentices through the program; Ritchie, in 1999, was his second, Bettman-Kerson his third in 2003. Kurjanowicz is Adams Granite Company’s in-house carver. He is standing in front of a memorial, carving its design with a pneumatic tool, when Ritchie and Vermont Woman arrive. Removing his respirator, he comments on how hard it is to attract apprentices. “I’ve tried as hard as I can to find capable candidates for this,"he says. Kurjanowicz rents this corner of the shed from Adams and also uses the space to sculpt his own work for Kurjanowicz Sculpture Studio (KSS). He shares the station with Ritchie, whose studio is called Bonnie Wee Arts, and Bettman-Kerson, a consulting sculptor for KSS. The two women also take on overflow memorial work from the older carver – the source of about half of Ritchie’s work. Kurjanowicz can’t think of a single gender-based difference between his male and female apprentices, all of whom have gone on to work for him for varying lengths of time. “Gender is probably the least obvious [difference]. The most obvious is personality, along with different skill sets, abilities, ways of learning," he comments. But just the presence of women in this industry has created a shift, he adds. “By introducing women [carvers], you force the environment to become more introspective. The perception, especially since Heather won these competitions, is that there is a female presence here."

|

|||||

Sue Higby administers the Semprebon Fund and since 2003 has directed Studio Place Arts, a community art center and gallery in Barre. She identifies more than a generic female presence since Ritchie and Bettman-Kerson’s arrival on the scene. Ritchie, says Higby, has shown sculptures in SPA’s annual stone-sculpture exhibition, called Rock Solid, every year since it began in 2000. Higby recalls that Ritchie’s submissions over the years have ranged from “these beautiful limestone vaginas” to “gorgeous mother figures with fabric appliqués," to bookends in the shape of breasts for the latest show. Sophie Bettman-Kerson, who has shown work in six Rock Solid shows, submitted a bust of a woman with her head thrown back and tongue out for last year’s exhibit that the sculptor describes as “almost erotic." The human body has long been a favored subject among stone sculptors, but Higby—a fabric artist—identifies the use of fabric appliqué on granite as a “classically female” idea. It’s also, in her art-world experience, unique. “The idea of putting something impermanent on something that will last forever—I’ve never seen anyone else do that," she says. |

|

||||

Ritchie’s path from her childhood in Barre to shaking up its native industry was hardly direct. Like many families in the area, she can trace her heritage back to the granite industry: Her grandmother’s maternal grandfather, a Scottish immigrant who arrived in the late 1800s, owned the local Littlejohn quarry. (Ritchie’s studio name, Bonnie Wee Arts, honors her Scottish heritage.) By the time Ritchie was born, however, her father was in the pharmaceutical industry. When the local high school, Spaulding, proved a poor fit, Ritchie transferred to the renowned all-girls boarding school in Troy, N.Y., Emma Willard. “That and my family being super supportive were really vital for me for becoming who I am and having the strength to persevere," she comments. Ritchie went on to earn a degree in studio arts at Bennington College. While there, she did an internship in the archives of the Vermont History Center—then housed in Aldrich Public Library in Barre—where she helped curate an exhibit on old-time carvers. Talking to living carvers around town for the exhibit, she began to entertain the idea of trying it herself. The response from the carvers, she recalls, was, “Couldn’t you find anything easier to do?" Ritchie returned her focus to painting during a post graduation residency at the Vermont Studio Center in Johnson. (She still paints, with recent works available at her Bonnie Wee Arts website.) She recalls that a fellow resident, a marble sculptor, offered to teach her his craft, but she declined.

Ritchie’s introduction to carving came when Aldrich head librarian Karen Lane put Kurjanowicz, a self-described bookworm and frequent library patron, in touch with Lane’s old intern. Kurjanowicz was looking for a carving apprentice. When he contacted Ritchie, she had been struggling to make it as a painter in New York City and was happy to be offered an out. There was something about granite that drew her in from the start, she recalls: “You have this very hard material that can also be very fragile." A sculpture a fraction away from completion could suddenly lose a chunk under an incorrectly applied sculpting tool. Ritchie learned to be “pretty picky about stone," examining the grain in detail before deciding to commit to a block of granite. For her beaver-dam bench, she spent an hour poring over one raw piece delivered for the project before deciding it would do. After working for Kurjanowicz for five years, Ritchie, by then married, took the next five years off. For one thing, she wanted to have children. “This work doesn’t lend itself to trying to get pregnant," she shouts over the roar, “or to being pregnant, or to nursing, or anything like that. It’s really a barrage on your senses." Also, sexism had taken its toll. Ritchie worked with Kurjanowicz in two sheds prior to Adams, following him from Desilets Granite Company in Montpelier to Rouleau Granite Company in Barre. Along the way, she encountered “inappropriate comments, inappropriate pictures” and other instances of sexual harrassment, intended or not. “Overall, the guys are really respectful, but it only takes one person to make it uncomfortable. That made it easy to check out for five years," she says. Ritchie, whose son and daughter are now eight and six years old, says the atmosphere is different now: “Those people have left." These days, the sculptor looks forward to escaping to work. “You try so hard to maintain order in chaos as a parent," Ritchie says with a laugh. “I can come here and make my own chaos."

Sophie Bettman-Kerson, of Middlesex, is leaning over a headstone that lies prone on a table between Ritchie’s and Kurjanowicz’s work stations. Barre’s other woman carver is using a pneumatic hammer and chisel to finish up a sacred heart, a key image in Catholic iconography. Setting her safety glasses up on her curly hair, the sculptor laughs about how she’s not wearing leather gloves like her mentor. (Kurjanowicz wears them to save his marriage, he jokes.) Like Ritchie, the skin on Bettman- Unlike Ritchie, however, Bettman-Kerson had to retrain as an LNA after Barre’s granite industry began its free-fall about a decade ago. Catholics were beginning to turn to cremation, and Chinese sheds had begun quarrying and carving memorials at a fraction of the price of Barre-made ones, relying on an underpaid workforce and government subsidies to undercut the American stone market. “The Chinese work was really hack," declares Bettman-Kerson, who had a solo sculpture show at Johnson State College’s Black Box Gallery in 2013. “For Barre, it was such an affront." Her response highlights the fact that, though stone carvers work in an industrial environment, they are ultimately artists. Bettman-Kerson and Ritchie often retreat to Kurjanowicz’ portable office, installed on the shed floor beside their workstations, to flip through the latest issue of Sculpture. (The office is also their only refuge from dust and noise, apart from stepping outside. Kurjanowicz built it after Ritchie, then his employee, told him she couldn’t hear the phone orders coming in.) “You get starved for real art," comments Bettman-Kerson, who has carved at least 100 sacred hearts.

|

|||||

Bettman-Kerson, Ritchie, and Vermont Woman pile into two cars with worn-out suspensions and power up a steep, wooded dirt road to Millstone Hill in Websterville. There, on one side of the road, a 150-year-old wall of huge granite blocks rises behind a scattering of birch trees. The stones are thought to be rejected pieces extracted from the abandoned, water-filled quarry a few steps away, according to Ritchie. The wall has been personalized by Barre’s carving community. Select stones bear free-form images from artists’ imaginations. A snout-nosed goblin leers in high relief from one block. A column and rough capitals are inscribed into another. One prominent vertical corner has been carved into the helmeted face and shield of a Greek warrior. At eye level stands Ritchie’s carving of a target, punctured with old, rusty chisels in place of arrows, and Bettman-Kerson’s delicate, low-relief rosebush. The wall serves as the site of a unique annual event called Rockfire, begun in 2012 as a summer solstice event to celebrate the region’s stone heritage. In the evening, carvings and sculpture are lit for viewing by candles and small bonfires. (Rockfire organizers are already planning for a June 27-28 gathering in 2015.) Imagining the event, it becomes easy to forget the physical work that goes into sculpting a material that has the highest density of any carvable stone. Granite weighs 190 pounds per cubic foot. Higby calls granite “the machismo stone." Once, at a demo, the gallery director recalls, she tried out a pneumatic hammer and chisel. She lost feeling in her arm after five minutes of attempted carving. “It’s brutal. It changes your body," Higby declares. Ritchie and Bettman-Kerson, however, never think to mention that aspect of their work. When pressed later, by phone, Bettman-Kerson says her shoulders were “football-player sized” after four years of full-time work. She left full-time carving in 2011; a year later her elbows still hurt. Standing beside their outdoor creations, the women are more interested in talking about art. Ritchie elucidates her target’s nod to Barre’s history. The chisels come from different periods in the city’s history, she says: Some were made by still-extant local fabricators—Barre City Tools, Trow and Holden—others by tool-makers long out of business. Bettman-Kerson explains that her rosebush is a tribute to the gorgeous cemetery carvings all around, dating back a century or more, which she calls “a knockout." As Higby declares of the two women carvers, “They are true artists. They have that fire in their bellies to create something that’s beautiful."

|

|||||

Amy Lilly, who lives and writes in Burlington, is associate editor of Vermont Woman.

|

|||||