Activist Art Transcends Climate Change

Eight years after Bill McKibben, the founder of the grassroots organization 350.org, penned this quote, artists of all genres are finally heeding his clarion call. Artists are convening in Montpelier this June to tell the emotional side of being human in a changing climate. What it is like to live with climate change? They are showing us their hope and despair in an exquisite outpouring of inspired, activist eco-art. McKibben set the stage with his "Art Sweet Art" essay. In 2009 he reflected, "It was probably the last moment I could have written it. Clearly there were lots and lots of people already thinking the same way, because ever since it's ...as if deep and moving images and sounds and words have been flooding out into the world. "That torrent of art has been, often, deeply disturbing. It should be deeply disturbing, given what we're doing to the earth," he concluded. The Goddard Gallery on Main Street in Montpelier is hosting the eco-art exhibit that continues through June 30, displaying 15 different artists in a full-throated visual chorus of response to climate change. Just the prologue to a month-long event, entitled "Unraveling and Turning" sponsored by 350VT.org, the visual art event will culminate with performing artists at a Cabaret on the statehouse lawn, June 15, from 6:00 to 9:00 p.m. A full program will follow inside the statehouse. Other events include poets and film gatherings. Altogether, some 50 artists with 30 different responses, all with ties to Vermont, are exhibiting and performing climate change-related pieces in June. Maeve McBride, who is Outreach and Systems Coordinator of Vermont's chapter of 350.org, said the idea for the event began with last year's fall cabaret in Burlington. From that success, "We wanted to move throughout the state into different local communities and have artists come together and do things related to this issue." Co-founder of the Fall 2012 Burlington cabaret, Kathryn Blume, recalled, "The cabaret had been an idea I was toying with for a long time." She recognized "the power of art to talk about things we can't necessarily talk about ...and (an opportunity) to express your feelings about what is happening." Blume is currently working on another project, Vermontivate, but says she thinks art necessary for people to move forward past recent extreme weather events like Tropical Storm Irene. Art can find a way to express the angst connected with a change that so many feel powerless to change. A Flow to Match Irene McBride similarly said it was their organization's wish to create a model for communities all over Vermont to express what climate change means to them, how it has affected them, and how, in some cases, like Irene's destruction of central and southern Vermont homes, changing lives. McBride said this notion of flowing to new communities got this year's co-producer Linda Patterson interested, and prompted her to reach out to Celina Moore and Peter Nielsen in Montpelier. Patterson, who has a Masters in Performing Arts from Bennington College, was involved in last year's Burlington cabaret, and recalled its birth and evolution, forward to this year's combined exhibit and cabaret. "I heard about Kathy Blume…She and I got together for tea and began comparing notes. We both discovered that, independent of each other, we had always wanted to do cabaret around environmental issues, so we said, 'Let's do it!'" They pulled in Jen Berger, a Burlington performance artist and activist, and creator of "Salmagundi: A Stage Where Change Takes Place," a series of fund-raising variety shows for community based non-profits. Berger describes Salmagundi as "a place for local artists to express themselves about social and political change on stage, and also for local activists and other people working on social justice to find a creative outlet." Together, the trio of women inspired one another, and successfully produced the first 350VT.org cabaret. Afterward, Patterson said they "...had the idea of taking it on the road to all communities in Vermont, and invite local artists to create a cabaret. Each community had a particular experience in climate change, of loss and destruction, of bringing people together," Patterson said. "It's an important way not only to reach out to communities and help them come together to express their experience, but to give local artists a venue to express it in a different kind of way." Patterson recalls, "I took a deep breath, thinking, I want to keep this going, and I put it out to the universe: which community would have a local person or two to help me produce it?" "Long story short," she laughed, "Celina [Moore] was singing with me in The Messiah last December and got all kinds of excited about it, and identified [the location]in Montpelier." Moore brought Peter Nielsen on board, and "we started planning it and," Patterson laughed again, "It's taken off—and I'm holding on for dear life!"

Our Choices The title of the month-long exhibit and cabaret, "Unraveling and Turning" came from the writings of eco-philosopher Joanna Macy, who speaks of "...the three stories or realities shaping our world today. Which do you choose to put in the foreground: Business As Usual in the industrial growth society? Or The Great Unraveling, as ecosystems and cultures fall apart? Or The Great Turning to a life-sustaining society? Each story is true and happening right now. The question for each of us is, which do we choose to identify with and devote ourselves to?" Celina Moore, mother of singer/songwriter Eliza Moore who will be performing "The Rose" for the cabaret, is a 71-year-old "maven of miracles and mayhem (who keeps) getting involved in these great big things." Her musical connections in Montpelier run deep and, while she says she is merely "a runner, a person to support and talk it out; I go along, smiling and cracking jokes," Moore is the hub around which the spokes of the wheel of this event turn. Many musicians came on board through her, she said. Co-producer Peter Nielsen, of HigherMind MediaWorks marketing and a Montpelier resident for 20 years, said the challenge was to build an audience. So they decided to do an exhibit and cabaret that would be "more like a month-long event...drawing from every possible art: music and drama and trapeze, sculpture and video, any form of art." "Bill McKibben's recognition of the need for artists to participate in this dialogue was a personal call to me," Nielsen said. "This is my job; this is being asked of me to do." He too felt the need to help shift the dialogue "into a more human-centered response to climate change. Our emotional response as human beings becomes a very powerful communication tool." Blume had also recognized early on the fundamental aspect of the arts' ability to change how people think. She saw the cabaret as an opportunity to change people's behaviors, to enable more sustainable choices for living on the planet. "When we engage with climate change, behaviors of people can change. There is a role for artists to play by talking about the personal and emotional experience which can be articulated better in arts," Blume said. "Artists of all stripes could come and bring a creative response to what we are going through." This year, performance artists, trapeze artists, musicians, poets, singers, writers, sculptors, visual and installation artists responded in droves, compelled to share work wrung from a deep response to climate change, held in anguished hearts and souls.

Living Possibilities Vermont painter Cami Davis, UVM art and art history lecturer and sustainability fellow, recalled reading McKibben's "Art Sweet Art" in 2005; it registered deeply within her. "He was saying, where is all the climate change art?" She asked herself, "Yeah. Why isn't there any?" Davis said she felt impotent in the face of the enormous challenges and changes facing the planet. That fall, a 49-mile walk from Ripton to Burlington was organized, "From the Road Less Traveled: Vermonters Walking toward a Clean Energy Future." Since she could not participate, she decided to create a series of installations along the walk. She described how she arrived at those works: "[The walk] was the first climate change activist event with Bill McKibben," she recalled. "There was something so powerful about that walk." She felt she had to find a way to do something. "I was out walking and feeling quite despairing," she said about the experience that led to her own turning. Suddenly, as she looked around her, she realized she was literally surrounded by thousands of cedar waxwings. "Their single trill was multiplied by a thousand, so I was literally vibrating." She laughed softly, remembering. "They were at my feet and in the bushes around me and up in the trees. There was this vibration, a feeling of just dissolving—there were no longer any boundaries between me and the landscape and the birds." She explained, "When I went home to look up their symbolism, it was 'transitions can come gently.'" She added, "Waxwings live in supportive communities where they feed each other, and they will tell other species where the berries are." She paused. "Not only can transition come gently; it can happen in supportive communities, together." She then did a series of 20 drawings on paper of cedar waxwings. These could not be installed along the walk, but the story and symbolism behind the waxwings piece was significant to her, so Davis framed "ten different configurations, leap frogging the walkers." Diaphanous fluttering waxwings were placed "in the field or in a meadow, in the woods or in a town they were landing in. It was a Gift for the Road." She called it, "Waxwing Medicine." Davis was one of the first artists to step up to McKibben's call to artists in Vermont. But as it turns out, she was not as alone as she thought. She began to meet other artists, with whom she collaborated; she has two pieces in the Montpelier exhibit: "Forget-me-not Petermann Glacier" and "Blackbird Singing in the Dead of Night," responses to receding glaciers and the quieting of the cacophony of bird song once familiar to Vermonters.

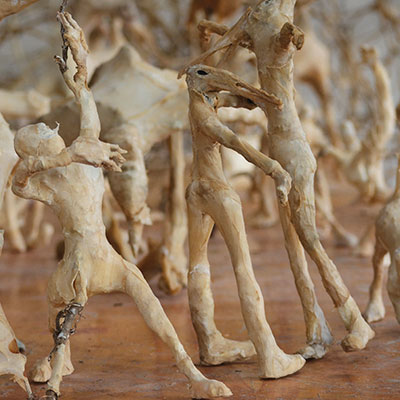

Artists of all mediums are transcribing their responses to waking up to a quieter spring, or witnessing the loss of polar bear habitat, or discovering more species gone extinct, or knowing that everyday somewhere in the world an extreme weather event is taking place that is wiping out life, livelihoods and homes. They speak of their despair, their grief. Some also speak of hope. Shelley Warren of Richmond and Ruth Wallen of Goddard College and San Diego are both installation artists expressing a sense of mourning or grief with their work. Warren proposed installing a large earthen mound directly onto the gallery floor, with a projection of a crouching, burning human figure. "The video displays the burning of the figure from the initial stages of the fire to the extinction of the figure in smoldering ashes. There will be a moment of darkness and quiet between each video looping." Wallen's piece reflects on her native San Diego County's population explosion and its serious impacts on threatened and endangered series local to the area. She wanted to provide an interactive public place for grieving, here, relating her work to changes Vermonters have experienced. Several trapeze artists and circus performers from the New England Center for Circus Arts in Brattleboro will be performing, and at least two, Megan Gendell and Lauren Feldman will be performing a trapeze act together. Their collaborative proposal for a doubles trapeze piece "juxtaposes the story of disaster with two individuals helping each other out in a time of need, fear, and distress." Gendell said this sense of people coming together in a community to help each other in the face of disaster was her impression and inspiration from witnessing Irene, having just moved to Brattleboro that week. "We imagine a future built on compassion and collective action in the face of precarious environmental circumstances." The Berlin, Vt.-based Moving Light Dance Company proposed, "...dancers moving in a circle representing species that are under stress due to climate change." The piece says and then asks, "As habitats change, more species' way of life or means of reproduction is being threatened. What separates us from them?" The dance answers, "Nothing. We are all one." Sally Linder, a painter and teacher who lives in Burlington, is heading to the Arctic this summer with National Geographic to study polar bears. Several pieces from her world-renowned series on polar bears, "Approaching the Threshold" are included in the Goddard exhibit; it is a series that is widely collected. Linder wanted to participate because she felt, "The naming was wonderful – unraveling and turning." She said she reminds herself often that, "I have to stay focused. That yes, there is an unraveling, but I must be very attentive to the growing movement of the turning." 350.org activism has elicited global responses to climate change. "If you stay in the unraveling you become paralyzed," Linder continued. "I think that the call initiates deep responses in the artists." Antibodies Rally In 2009, McKibben wrote, "Artists, in a sense, are the antibodies of the cultural bloodstream. They sense trouble early, and rally to isolate and expose and defeat it, to bring to bear the human power for love and beauty and meaning against the worst results of carelessness and greed and stupidity. So when art both of great worth, and in great quantities, begins to cluster around an issue, it means that civilization has identified it finally as a threat." Grand Isle sculptor Riki Moss, who created amorphic creatures with handmade ecopaper in response to this quote from McKibben, said of her work, "My creatures sense trouble, they're out on parade, exposing themselves as they drift in and out of existence. Look at me, take heed, goodbye." She stated, "We humans are part of everything, morphing, dissolving, evolving, as our planet spins out its unfathomable destiny. The universe is always in flux, climate is always changing and at this moment, [we] conscious[ly] understand that our careless plundering of planetary resources endangers our very existence. If we leave it to officials to map out solutions, we can expect a future as gridlocked as we are now.... "What we need is a deepening conversation, to envision a creative line of questioning to lead us to a creative future. The artists are the envisioners, provoking a new narrative of our life on earth. I'm eager to join in." An Australian professor of sustainability and the environment, Glenn Albrecht, in 2007, coined a new word: "Solastalgia is a new concept developed to give greater meaning and clarity to environmentally induced distress. As opposed to nostalgia—the melancholia or homesickness experienced by individuals when separated from a loved home—solastalgia is the distress that is produced by environmental change impacting on people while they are directly connected to their home environment." Artist Jen Berger mentioned this word, "solastalgia," as did many of the artists Vermont Woman spoke to. Berger said of the caberet, "The idea is to create a space to talk about issues, a way of working on social development through ...art, not just everyday journalism. Active art is a form of voice. And ...artists use their skills in thinking about topics." Midsummer Soulfest "It's way more than a cabaret," Celina Moore said. "We're going to have midsummer on the state house lawn at the Vermonters' house and artistically express and be aware of the world. Human beings are very nearsighted." Moore continued, "There is an artist in all of us with a need to express ourselves about our fear and the situation. And the artists enhance the visibility of it in a very dramatic way. It's an incredibly beautiful idea," she enthused, excited to spread the idea "around the state and around the world." With this month long opportunity for exposure to dozens of artist's responses to climate change, there can be no doubt, future generations will know what it meant—on a human level—to live through cataclysmic upheavals as climate change happened.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allison Teague is Vermont Woman's environmental writer and a talented artist and photographer. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Diversity Speaks

Diversity Speaks