Memory Care in Vermont:

Understanding Alzheimer’s

and Related Dementias

By Roberta Nubile

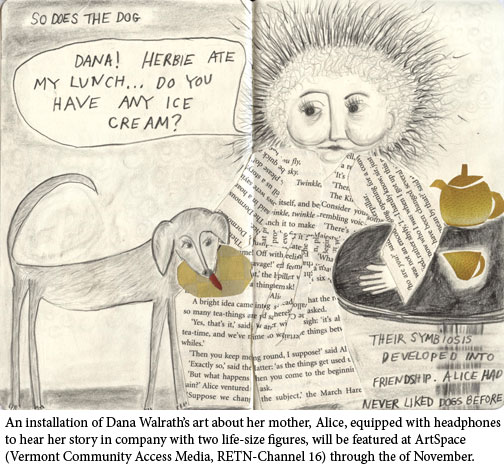

Dr. Dana Walrath’s mother, Alice, is 77-years old and has Alzheimer’s disease. Dana and her family cared for Alice in her home in Underhill for over two years. In her blog, called “Alzheimer’s through the Looking Glass,” Dana, a medical anthropologist and professor at the University of Vermont, Department of Family Medicine, writes:

“‘Dana, am I going crazy? You would tell me if I had lost my marbles, wouldn’t you?’ I’ve heard these questions many times. Repetition. Anyone who lives with Alzheimer’s knows from repetition. As her rudder, I always supplied my mother, Alice, with the same steady answers. ‘No. You’re not crazy. You have Alzheimer’s Disease so you can’t remember what just happened.’ ‘Oh. I forgot. What a lousy thing to have.’ ‘Would you like a cup of tea?’ ‘Ohhh, I would love a cup of tea.’ This ritual soothed us both. As an anthropologist, I know from ritual and how it uses repetition to soothe worries, to fill in the unknown, to make things better.”

Alzheimer’s is a progressively worsening brain disorder which affects memory and intellectual abilities enough to interfere with daily life. Brain cells die over time and lead to specific tissue abnormalities identifiable on autopsy. While the cause is not fully understood, genetic, environmental and lifestyle correlations have been identified. Medications and natural treatments exist to treat symptoms in the early stages, but they are widely considered to be ineffective as the disease progresses. There is currently no known cure.

Dementia is a general term for a group of brain disorders. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia. It affects nearly 12,000 Vermonters, and 5.4 million people in the U.S. Two-thirds of these—3.4 million—are women.

It is the sixth leading cause of death among Americans, and according to Susie Hennessy, RN, and team manager for Palliative Care and Hospice of the Visiting Nurses Association of Chittenden and Grand Isle Counties, is marked by a ”decrease in functionality, such as eating, swallowing, and moving.” The major complication of the loss of swallowing function leads to death by aspiration pneumonia, or, as most of us know it, when food goes down the wrong pipe into the lungs.

Martha Richardson, Executive Director of the Vermont Alzheimer’s Association, clarifies the commonly used term Alzheimer’s and dementia. “Dementia is the symptom, and because seventy percent of people with dementia have Alzheimer’s, most often just Alzheimer’s will be referred to.” There is no one typical Alzheimer’s patient. As Kathi Monteith, Director of Community Relations at the Arbors, a memory care facility in Shelburne, says, “If you know one person with dementia, you know one person with dementia.” Montieth says that while a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and related dementia can be helpful to some families and unimportant to others, no two patients will exhibit the same symptoms. There is no one-size-fits-all plan of care.

Diagnosis and Treatments to Know About

Previously the diagnoses of Alzheimer’s could be made only by autopsy. It is now agreed in the medical community that a diagnosis can be made with accuracy by a medical exam, which includes a full physical, as well as memory and functional tests. According to Marvin Klikunas, MD, Internist and Geriatrist and Associate Professor at the University of Vermont’s College of Medicine, “Any physician who is comfortable and understands the assessment tools for diagnosing dementia can make the diagnosis, while some physicians may feel more comfortable referring your family member to a memory care specialist.”

Conventional pharmaceutical treatments for Alzheimer’s include medications to improve memory loss, sleep disorders and behavior problems. The main category of drugs includes the cholinesterase inhibitors, which work by boosting the levels of a chemical messenger involved in memory. Anti-psychotics, anti-anxiety and anti-depressants may be used for managing behavioral issues.

The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCAAM) convened by the National Institute of Health(NIH) does not currently endorse alternative treatments, such as vitamins, herbs and fish oils to treat Alzheimer’s and other related dementias. It cites inconclusive research, but also points out the need for more rigorously designed clinical trials in this relatively new field.

In the practice of naturopathic medicine, however, prevention is the favored approach before or in conjunction with pharmaceuticals. Dr. Donna Powell, Naturopath at Health Resolutions in Burlington states, “People should exhaust [naturopathic] options when combating the early signs of aging such as memory loss and balance issues. When we give B12 shots, you can see remarkable changes in memory, balance and anxiety. We also use polypeptide complex, which can stimulate acetylcholine production in the brain with very good results.”

Because of the vascular risk factor in connection with Alzheimer’s, eating a heart-healthy diet and staying fit are also prudent choices in prevention. What is agreed upon, however, whether conventional or alternative practitioner: there does not seem to be a magic pill to stop the progression of Alzheimer’s in its later stages.

Walrath’s background in medical anthropology created a unique lens through which to view her mother’s disease; she was a key developer of a medical school curriculum encompassing humanism, cross cultural healing, and integrative medicine at the University of Vermont, and co-authored a major anthropology text.

“There doesn’t seem to be ‘Alzheimer’s’ in Native American cultures,” says Walrath. “If your culture is comfortable with people being in different realities, it might not be that there is anything to do. They treat [memory loss] differently. In the medical anthropological view, you take whatever you can from medicine, but other journeys are going on. When Alice lived with us, what I needed to be was not her doctor, but a happy, kind, and compassionate person who knew her lifeline. I know the biomedical approach says ‘Let’s cure something,’ and, I knew this fell into ‘We can’t make this go away, so just make life good.’ So I put all of my energy into that.”

While her mother Alice was most comfortable with a biomedical approach to treatment, Walrath says, “The Alzheimer’s allowed her to be open to other approaches. The biomedical model can only go so far.” Walrath sought out Vermont mind-body therapist Martha Whitney to utilize Hakomi therapy, a somatic approach to assist with her mother’s communication skills as words began to elude her. Together they developed a series of motions her mother could use when words failed her, which Walrath says are tools they still use today.

Whole Sets of Family Decisions

Diagnosis and treatments are just the tip of the Alzheimer’s iceberg. The more complex issue—how to care for your loved one with Alzheimer’s—becomes a dynamic set of decisions made through the family, weighing the benefits and demands of the home caregiver role, versus a residential memory care facility. In the home, a menu of supportive services is available through home health agencies. These agencies can assist with non-medical care ranging from adult day care to transitions such as waking up or going to bed, from light housekeeping to companionship, and anywhere from a few hours to 24-hour care.

The stress of caring for a loved at home can be great. Amy Feeney, president and owner of Armistead Caregiver Services serving northern Vermont and western New Hampshire, says, “Typically our initial contact is respite for family when the patient is in generally good physical condition. People don’t tend to call us until they are worn out, but that’s changing. People are being more proactive.” Armistead also offers support groups for patients and families, which include education. Despite the stress involved in caring for a loved one at home, for some families it is still the preferred choice.

Carmen Gale of Barre, now 78, was in her early 50s with grown children and poised to enjoy her retirement after years as a school nurse, when her mother Adrienne Couture was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. She needed full-time hospice care. Adrienne had been diagnosed with dementia five years earlier, and her family endeavored to keep her in her home. Gale willingly took on the role of caring for her mother full time, with respite at night.

Gale recalls, “My mother would say, ‘Carmen’s car is always here but I haven’t seen her in a long time.’ I remember one time, when I stood in front of her and yelled at her, ‘Mom, it’s me, I’m here,’ and she started to cry….I should have had patience, but the situation got the best of me. I felt like I was working my butt off and she didn’t know it was me. Caring for my mother, who didn’t recognize me as her daughter, it cut to the core. But I wouldn’t have traded it for the world. I felt like I was the lucky one. I was able to take care of her.” Gale cared for her mother for 3 months before she passed away.

For others, the decision to care for a loved one with Alzheimer’s at home must be weighed against the needs of a growing family. Deb Sherrer, 51, of Shelburne, grappled with the decision. “It was a really difficult and challenging process to be clear within myself, and [know] what my own boundaries are and how that fit in this phase of life. How I want to be present to her and where I don’t and living with that. I have seen my sisters sacrifice their health and expressed my concern about that. I have to respect they are in their own process, and I have to hold my own place. It’s a practice, not that you reach this point and it’s done. The whole thing is a practice.”

Sometimes a family will care for a loved one at home until there is a breaking point, which forces them to reconcile the demands and toll on their family life. Walrath cared for Alice until issues around incontinence and aggression proved too much. Alice was moved to a locked Alzheimer’s facility in New York State near another daughter. In her blog Walrath wrote,

“As a good member of my culture, I knew that ‘recognition’ was the socially legitimate threshold for changing the rules of care. When Depends™ could not solve the problems of the body letting go, Peter and I came to the end of being able to continue with Alice in our home. The transition was OK—we had rehearsed. A few nights before Alice moved, she gave us a story to explain the transition to others: I had just tucked her into bed and had gone down the hall to my room when I heard her calling loudly. As I ran back to her room, I could make out her words. ‘Lady, lady, lady!’ I opened the door. ‘What’s up, Na?’ ‘I just wanted to know your name.’ ‘Dana.’ ‘Pretty name.’ ‘Thanks. You gave it to me.’ ‘And if I just call, you’ll come?’ ‘It might not be me, but if you call, I promise you, someone nice will come.’ ‘That’s good. Thank you. I’ll sleep well knowing that.’

A list of residential memory care facilities can be found through the Vermont Alzheimer’s Association database. Memory care facilities will vary in the amenities they offer, but often the most up-to-date methods of caring for Alzheimer’s patients are standard. These include a peaceful, low stimulus atmosphere, Dining with Dignity programs (an example is pureed chicken put into a mold to resemble a chicken breast), colored walls to help differentiate depth, and safe places to wander both inside and out. The majority of services and facilities are private pay, with some Medicare, long-term care private insurance, Medicaid and sliding scale options available.

Understanding options for care and how a family can afford it can be an overwhelming task. An excellent place to help sort through all the information is the Statewide Senior Helpline which directs you to your geographical Area on Aging. Another resource is the Vermont Alzheimer’s Association (see resource list).

Opportunities for closure in complex relationships with an Alzheimer’s spouse or parent may or may not exist in the family caregiver role, or may be fleeting at best. Sherrer describes the grieving process as a slow letting go, parallel to the loved one’s decline, and the choices inherent in that time. “At some point there is some functional death when they don’t know you anymore, and the relationship is forever altered. It’s a juncture you come to when the relationship you knew no longer exists. Before you get to that point, in this long goodbye, you look at the quality of any unfinished business in your relationship and can make a conscious decision if there is anything you want to finish—because you’re going to reach a point where you can’t process it with that person.”

Some caregivers describe the gifts in caring for their loved one. Linda Patterson, 58, of Charlotte had a mother who died of Alzheimer’s-related causes, and has a father with Alzheimer’s who lives in residential care. “I was talking with a friend who’d also had a parent with Alzheimer’s, and we were talking about the challenges of caring for our parents. He said to me, ‘You will learn about yourself from your father.’ This turned out to be quite true. During a phase last summer Dad became extremely agitated and wanted to move out, using words liked ‘feeling trapped like an animal.’ I felt myself identifying with that concept in a bigger frame of feeling trapped in our lives, in terms of social norms, relationships and economic constraints, and it helped me develop greater compassion for him. As long as I could, I took him on trails, as he was a naturalist, a bird and tree person. We would go out together and he would say the trees are my friends. He would have a visceral connection nature—a mirror for my own feeling. Dad was able to put into words what I could not.”

And Walrath writes of her mother: “‘Dana, why are you so good to me?’ I had just finished helping Alice get dressed. Picking out clothes to wear and getting them on was long-since-too hard. Now I stood behind her, brushing her hair as she sat at her dressing table. Our eyes met in the center of the three-part mirror that had stood like a folded screen on her dressing table for as long as I could remember. ‘Because you are my mother.’ Big pregnant pause. ‘I’m your mother?’ And another. Alice turned to face me. ‘Who’s your daddy?’

‘You were married to Dave. You had three children. Mark is the oldest, then me, Suzy is the youngest.’ ‘Ah, yes. I remember.’ Alice turned back and I kept brushing, watching her through the mirror. She looked up and found my eyes in the reflection. ‘I wasn’t very good to you. I’m sorry.’ Unfinished business. That’s one of the reasons she was here living with us. But I never imagined I would hear these words stated so simply. ‘Thanks.’ ‘So you forgive me?’ ‘Of course.’ On an intellectual level, I had forgiven her years before. ‘How come?’ ‘Because you did the best you could.’ I knew that if I wanted it, Alzheimer’s would let us have this conversation every single day.

Research, Education and Open Dialogue Ahead

According to Richardson of the Vermont Alzheimer’s Association, breakthroughs in early detection may be hopeful. “New science is showing that they can see signs and biomarkers that are depicting preliminary proteins that are strong indicators of clinical Alzheimer’s, and showing up 10-15 years before someone exhibits symptoms. If we have the ability to change the course of the disease before any one sees symptoms, this is an incredible moment for change in research.”

Richardson stresses the urgency of education, open dialogue and research funding for Alzheimer’s. She points out the current trend in Vermont is “scary, in light of the growth of the baby boomer generation and our aging population. By 2025, we will be up to 20,000, and we can’t afford to care for these people.

I’m in my 50s’, and I remember when the word ‘cancer’ used to be whispered. But being afraid of the disease is not going to stop it. Alzheimer’s is not a dirty subject, and it is not going to go away. Vermonters are a proud community. While people love to help, people don’t like to ask for help. People need education and their questions answered. I see so many people who find it hard to ask for help, as the stigma and embarrassment comes into play. Real change won’t happen until we are willing to speak about it. If we invest in research we would be able to change the outcomes and quality of life. We are great at longevity, but longevity without quality of life is not a great bargain. Until we find a cure, we need to focus on supporting caregivers and people with dementia in making it through the disease process.”

Roberta Nubile, a freelance writer and registered nurse, lives and works in northern Vermont.

|