Making the Economy Our Own

The most important thing women need to know….

By Rickey Gard Diamond

Do your eyes cross when you read about the economy? If so, this article is for you – the first of a series to engage women in Vermont’s economic thought and action.

I’ve been reporting on the subject of women and the economy for over 30 years, and am familiar with the field’s intimidating language, complex and uninviting. Yet if we women ignore the question – “What exactly is “the economy?” – we do so at our own hazard. Finding answers may be difficult, but I’ve discovered one troubling and consistent truth. However the economy gets defined, women do not own it.

This is where I’m supposed to say women have made big inroads the past 50 years. We have. Fifty years ago, women began entering professional fields – including economics – in numbers large enough to begin to make a difference. Vermont’s Stephanie Seguino, a professor of economics at the University of Vermont (UVM) and an associate dean, is a great example. She examines racial and gender disparities in the context of macroeconomics, meaning the financial underpinnings of nations, such as central banking and trade theory.

Economic stories about women as a group often talk of our getting the short end of this present economy’s stick. To be positive about women’s economic carrots the past 50 years:

- More women today work outside of the home, even at banks, and make and get loans and mortgages. More women have credit cards. However, we’re generally not on the boards of banks or owners of them.

- More women have gone into business for themselves. Many are micro-businesses to enable working at home. However, women still struggle to get business loans for their entrepreneurial ideas.

- More Vermont women than men now have college degrees! A female college grad even makes a few hundred dollars more than the Vermont guy who graduated from high school. Although still close to $20,000 a year less than a male college graduate.

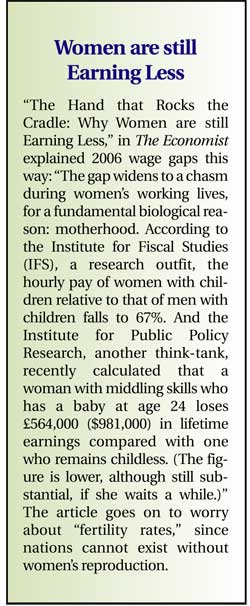

- More families have two working parents (and need them). More mothers of very young children work more hours than ever, while desperately seeking affordable childcare. Without motherhood, there could not be an economy. Yet this current economy guarantees moms a lower wage and more expenses – plus guilt pangs for lacking superpowers.

That’s the good news, and women continue to enter the field of economics in growing numbers, according to Seguino, who is currently president of the International Association for Feminist Economists (IAFFE). Most economists, however, are not women, or people of color. “Most are a particular class of a particular race of men,” Seguino stated, something that also remains largely true for investment bankers, financiers, corporate deal-makers and CEOs. Numbers of women in brokerage firms, investment banks, and asset management on Wall Street have actually fallen the last ten years, a trend The Wall Street Journal called “alarming” in a recent article. Would more women on Wall Street make a difference? Perhaps, but only if the game’s rules admit the economy is more than a game and affects lives.

Getting Started

Before we can increase women’s ownership of our national and state economy, women need to face our cost-effective selves in the mirror. Women constitute half of the world’s population, perform nearly two-thirds of the work, receive one-tenth of the world’s income, and own less than one-hundredth of the world’s property. We are basement bargains, much of our work unpaid and unaccounted for in this present system.

“All economic problems have solutions,” Seguino said to me over lunch, in a voice that rang with reassurance. Seguino’s career began as an economist for U.S. development in Haiti from 1984-88. In the 1990s, she joined the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine to research working women, followed by economic research as a Fulbright Scholar in the West Indies in 2000.

Not only an internationally respected professional, Seguino is a mom, and active in her local school, where she says she’d like to see increased diversity, a goal she pursued at UVM as dean. “Inclusion matters!” she says.

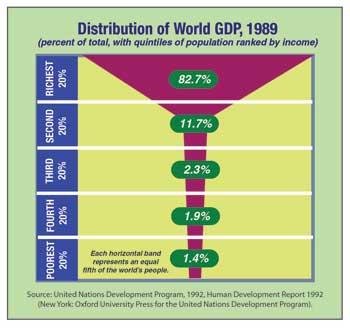

The single most important thing Vermont women should know about the economy, according to Seguino, is that inequality is increasing, not decreasing. “We’ve seen an explosion in the growth of economic inequality since 1960,” she answered me without hesitating. “If we look at income ratios around the world today, we can see that for every $1 the bottom quintile of the population (20 percent) earns in income, the top 20 percent make $105. This is huge,” says Seguino, referring me to a graphic from Isabel Ortiz at the United Nation’s UNICEF that illustrates this.

Statistics from UNICEF demonstrate the marked disparity among GDPs (Gross Domestic Product) worldwide, but the U.S. GDP shows a comparable inequality. Most significantly, the total size of U.S. GDP has tripled in real dollars since 1960, thanks in part to increased productivity, yet incomes have stagnated for most American households. The U.S. Census described the income distribution this way: 20 percent of all money earned goes to just six percent of all Americans.

“And this is simply a measurement of income,” explains Seguino, “not a measurement of assets, such as property, businesses, stocks, bonds, where we see an even greater inequality.” Looking at wealth, not just income, the top one percent of the population in 2004 owned more than a third of U.S. net wealth and the top five percent owned 60 percent. Such reports, however they are shaped and sliced, are not disputed. Take a look at this national pie for 2004, which describes wealth, not just income, and its similar lop-sided statistics.

Now imagine this more personally. Picture 100 chairs in an auditorium, with you and 99 other people attending the most important event of your life. Bill Gates comes in and reserves 34 chairs for himself. Oprah Winfrey and eight other billionaire friends get 37 chairs to share among themselves. The last 90 people who come in (us), get to negotiate and argue over sharing the last 29 chairs. You and three of your neighbors will have to share one seat – somehow.

The trouble is we are not really playing musical chairs here with policies that favor the rich, but are undermining American livelihoods and a functioning democracy. Statistics on national income distribution are collected by the United Nations and by the CIA, both interested in monitoring political unrest which is frequently caused by wide income inequalities. These numbers, also collected by the U.S. Census, show the U.S. aligned, not with our European Union allies – all of whom have national policies that help level economic playing fields – but with less politically stable countries. American politics have become as polarized as American incomes.

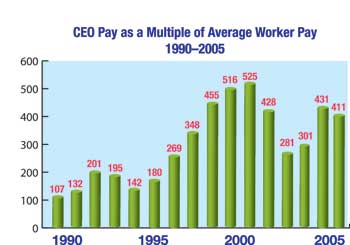

Without governmental limits, international corporations pursue profit without regard for democratic concerns. Another good indicator of the growth in inequality, according to Seguino, can be measured in CEO pay in relation to workers’ pay. Though Vermont isn’t home to many S&P 500 companies (like IBM), national trends in CEO pay set a precedent and help create a business environment that accepts such disparities as “natural.” CEO salaries have dropped by nine percent since the 2007 bank bailout and Congressional limits, but their pension benefits have increased by 23 percent. (How is your pension doing?) CEOs can expect to get bonuses, stock awards, option awards, non-equity incentive plan compensations (whatever those are) and unspecified “other compensation” of $235,232, according to a 2009 survey taken by the Institute for Policy Studies. However these perks add up, the most recent CEO pay at the top 500 companies averages a cool $9.25 million/a year. The salaries of working women and men were squeezed to find this money. Often their jobs got sent to even poorer workers offshore.

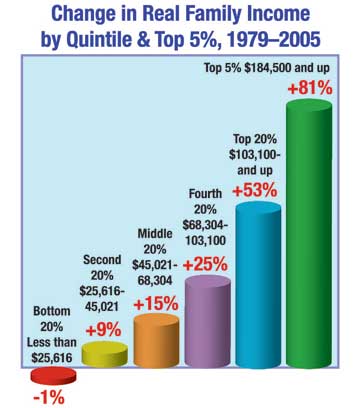

In which quintile of the economy would you and your family most likely fit? The graph below charts dollar amounts for five quintiles, and also for the top five percent. It documents a 26-year trend of losses for the poor and tiny gains for working class and middle-class Americans—before the Crash of 2007. Remember the GDP in this same period tripled in real dollars. Many Americans are now much worse off.

Women, facing wage discrimination, job segregation and the added expectation of unpaid household work and care-giving, will not often rank in the top 20 percent, fewer still among the top five percent. (Oprah did make #131 billionaire in Forbes 2010 Richest List, among a handful of “self-made” women, Fortune’s word, not mine.) Education in the U.S. makes a difference, but gender and race matter more for household income. In Vermont, where poverty is white, most often the poor are children and their moms. They and the second quintile have fared the worst with contemporary policies. Nevertheless, most Americans are wealthy by world standards.

“For any economy to really function well, it must provide people with economic security, but with this present system, we force people to play economic roulette. Jobs are increasingly insecure and short-term,” says Seguino. “Women are very vulnerable in this economy, especially those who are mothers. Employment practices make it difficult for women to juggle parental responsibilities and the need to earn a living. Because of this, women disproportionately are hired part time, and thus there is a wide income gap between men and women.”

About this pattern of economic imbalance and the absence of women’s perspectives in the halls of power, Seguino says: “Structurally, what this means is that those who benefit from this inequality can influence politicians. This is happening around the world and it is happening here in this country. This undermines democracy.”

Interestingly, though this present economy’s dollars go upwards to international CEOs and Wall Street and investment bankers, women around the world are largely responsible for the production rewards they enjoy. “The Importance of Sex” in The Economist (2006) credited women with the lion’s share of global economic growth, noting, “Add the value of housework and child-rearing, and women probably account for just over half of world output. It is true that women still get paid less and few make it to the top of companies, but, as prejudice fades over coming years, women will have great scope to boost their productivity—and incomes.”

Um. Maybe. But women already have been waiting for, hmmm, about 3,000 years. Meanwhile, our lower wages, whatever our hours worked, really hurt Vermont families. According to Vermont’s Commission on Women, “The wage gap is real in Vermont. In 2006 the median wage for a man was $16.08/hour while the median wage for a woman was $13.82/hour, resulting in almost $5,000 less a year for the typical Vermont family to take care of basic needs.”

Yet as Seguino also pointed out, in this economy wages are relatively small potatoes. Assets and property and “financial products” matter more. Take another look at that UN graph of GDP, a measure of national economic product and income. Do most women you know, including the young women who aren’t going to work on Wall Street, crave a ride to the top of this economic pyramid? Must success come at the cost of the majority of women who do the lion’s share of “output” in the world’s current economic system? Or is there a better way to operate a more woman-friendly and far less volatile economy?

Stay tuned for future issues: “Meeting a Crisis in Care” (February/March), and “Creating New Economic Measures” (April/May).

Rickey Gard Diamond, contributing editor at Vermont Woman, lives and writes in Montpelier.

|